30 Months of Tanren

By Michael Shane

This article was originally published by Fudokan Dojo.

Our dojo here in New York City was suddenly closed.

It was the spring of 2020, and the COVID-19 pandemic had upended life for everyone. I was lucky to be safe and healthy, and after some time I realized that this upheaval might contain an opportunity to find something that was missing in my swordsmanship. At this point in my study of the sword I had spent years trying to understand what I now know as shisei (姿勢) — “the capacity of posture to generate power”. I understood the concept intellectually, but I had failed so far to connect with it in a practical way. So I emailed John Evans sensei out of the blue to ask if he would take me on as a long distance student. He was kind enough to say yes.

John Evans sensei holds the rank of Kyōshi 7th Dan in Nakamura Ryū Battōdō. He trained extensively in Japan for over a decade, including with Nakamura Taisaburo sensei. He is the founder and chief instructor of the Fudokan Dojo in London, UK, where he has taught the curriculum of Nakamura Ryū Battōdō and the International Battōdō Federation alongside Kurikara Ryū Heihō since 1996. He is the author of Kurikara: The Sword and the Serpent and one of the few teachers of Japanese martial arts today who offers a systematic curriculum of internal practice.

The tanren (鍛錬) is part of the curriculum of Kurikara Ryū Heihō (倶利伽羅龍兵法), a syncretic school of Japanese swordsmanship with roots in shugendō (修験道 / mountain asceticism). The word “tanren” means “forging” and, just as in the process of creating a Japanese sword, refers to the application of heat and pressure to expel impurities and imbue the subject with strength and flexibility. To the casual observer, tanren may resemble yoga, qigong, and other practices that traveled from India through China to Japan over time. The tanren practice of Kurikara Ryū is a rare example of a systematized curriculum for internal cultivation in Japanese martial arts. When I wrote to Evans sensei, I knew the tanren would challenge me, but I had no idea just how comprehensive the scope of those challenges would be. I soon realized I was not just doing esoteric calisthenics and breathing exercises. Approached with the proper mindset, the tanren confronts you with your physical, mental, and emotional blockages wherever they might be. Some of these challenges are common among students, but everyone’s path to dissolving them is unique.

For those of us looking to go deeper in our study of the sword, our Western lifestyle — from how we work and move to our learned intellectual, emotional, and dietary habits — presents major barriers. Many of us sit at desks all day, hunched over keyboards. The tanden (丹田 / body center) never develops, rendering it inaccessible, and the lower body weakens. The joints which should be the most flexible when wielding the sword, like the shoulders and hips, are often the most frozen and blocked. We rarely squat or get close to the ground. And in the dojo we are habitually drawn into intellectual overanalysis.

All of this contributes to misuse of the upper body and the arms when cutting and moving with the sword. Needless to say, achieving a state of true freedom with the sword, what Nakamura sensei called jiyu jizai (自由自在), is impossible under these conditions.

As it turns out, the timing of my email to Evans sensei was lucky. Due to the COVID lockdown in the UK, he had recently begun virtual tanren classes for his students, and he invited me to join — if I could manage my way through some preparatory exercises from 3,500 miles away.

The temporary closure of my dojo allowed me to focus on these exercises without temptation to go looking for “progress” with a sword in hand. I realize now that this is exactly the circumstance I needed; swinging a sword at the time would have been counterproductive. In fact, during six months of intense virtual training, over 60 Fudokan Dojo sword students improved significantly despite not having access to their swords in the usual manner.

I practiced the tanren preparation sequence daily for a couple of months, during which I spent all of my training time on the ground, familiarizing myself with abdominal musculature I did not know I had and parts of my sympathetic nervous system I did not know I could explore.

One of the first things I learned was a breathing practice called uddiyana, which literally means “flying upward.” It is most often encountered in Hatha yoga, but is also foundational in tanren. Performed properly, uddiyana refers to the “empty” phase of omoni kokkyu (重荷呼吸), the “breath of the heavy burden”. As one component of tanren, uddiyana can begin to transform the breathing process by helping to move energy from the tanden into the spine and legs.

The early stage of the tanren curriculum creates scaffolding that replaces counterproductive physical and mental habits later in training. In one of my first sessions, Evans sensei said, “we are not mechanically forcing or imposing a physical or mental connection between the outer and inner body. Rather we are re-learning and allowing natural functional relationships to reemerge.” During these early months, I learned that building this foundation was less about forcing things in than letting things go. My breakthroughs always came during moments of release in which there was commitment and acceptance, but not exertion.

After a few months, having acquired basic core strength and abdominal control, I moved on to the core tanren curriculum, which consists of a long kata in three parts. Mastery of this material culminates with the practice of kujaku (孔雀) or peacock pose, called mayurasana in Hatha yoga.

The three parts of the tanren kata are called shōken (小圏), kikō (氣功), and daiken (大圏). The name of the middle section, kikō, is the Japanese word for qigong, which speaks to influence of the Chinese internal arts in the tanren.

During the shōken, deep, narrow squatting actions are combined with omoni kokkyu. Practicing the shōken helps the body learn to coordinate leg power with abdominal breathing. Evans sensei writes that, “in the squatting and rising movements not only do the two physical realms of the human structure integrate but so do the upper and lower mental structures — the cerebral functions and the limbic functions.” Establishing this working relationship is a foundational aspect of swordsmanship. In this way, the shōken is about building power in the lower body and reshaping the role of the mind in the process.

During the kikō, one spends long periods of time in static, confined poses that tax the legs and the mind, leading to further development of the tanden as a central junction for the flow of energy. After sufficient practice, discomfort gives way to new physical sensations and greater sensitivity to the emotional mind from moment to moment. It is not uncommon for advanced tanren practitioners to experience momentary waves of emotion during practice, and learning how to let these currents simply flow by is an important part of the training. In this way, the kikō section of the tanren collects the power generated during the shōken and shapes it.

Once the shōken and kikō have been mastered, the daiken finally introduces movements from swordsmanship. This practice combines the breath and leg power of the shōken and the stillness of the kikō with the enkeisen (円形線), the circular path of the sword in motion. During the daiken, steel rods (tetsubō / 鉄棒) or a heavy wooden training club (tanrenbō / 鍛錬棒) stand in for the sword. Under extra weight, the slow movements of the daiken allow the abdominal brain time to feel what is happening internally so that proper integration can be learned and later reproduced at speed with sword in hand. The daiken harnesses the power generated by the shōken, which was contained by the kikō, and releases it for the first time into the shape of swordsmanship.

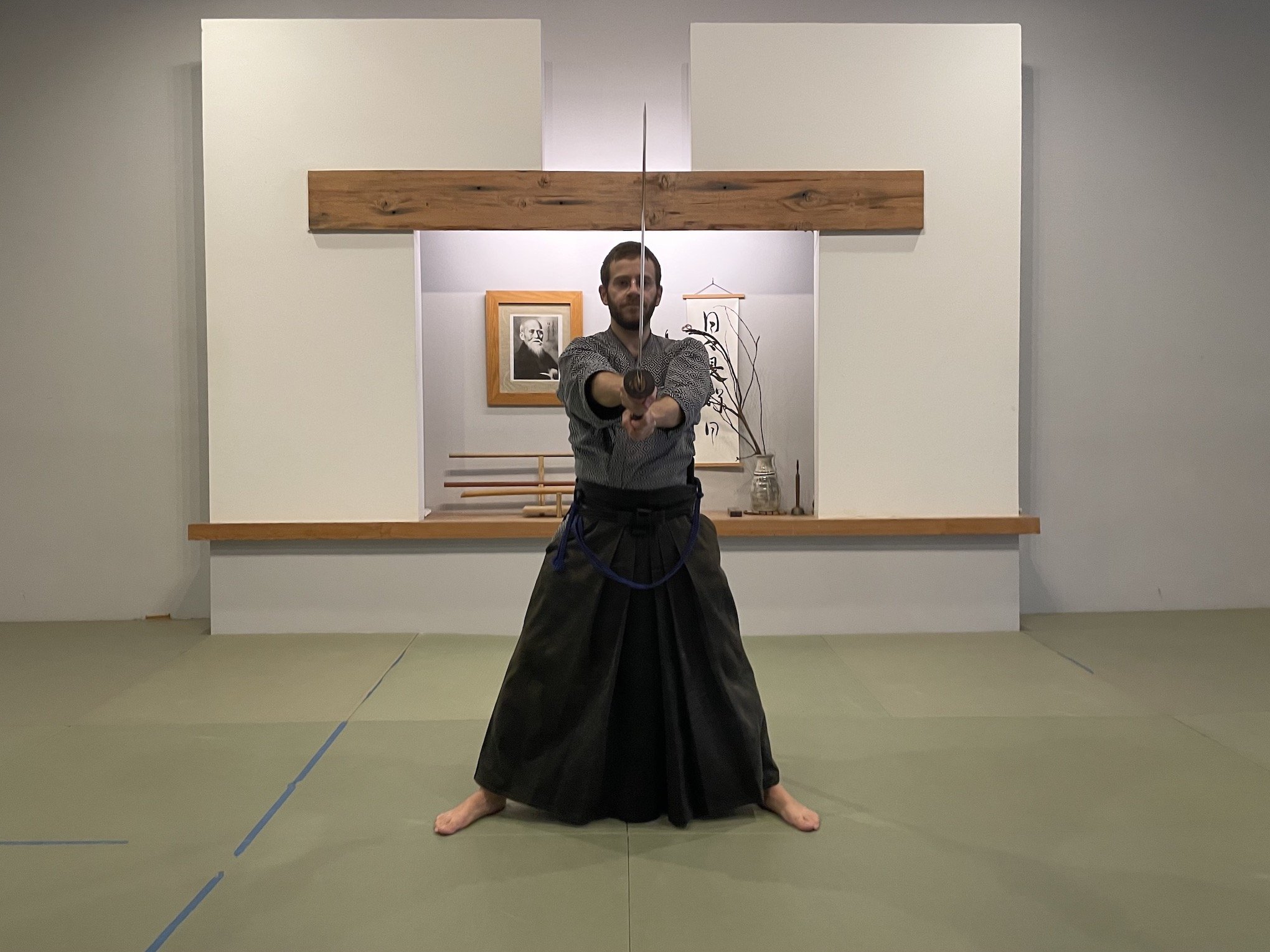

Excerpts from the daiken with tetsubō, tanrenbō, and sword

The shōken, kikō, and daiken are a microcosm of the fundamental elements of swordsmanship: generating power, containing it, and releasing it purposefully and without physical tension or mental agitation. And like the path of the sword in motion, the tanren practice is circular. Each element reenforces the others. Hida Harumichi describes the ideal outcome as “reaching that stage in which the upper body, which is by nature empty (虚 / kyo), remains empty, the central body, which is substantial (実 / jitsu) by nature, is made substantial, and the lower body, which is empty by nature, is made substantial.”

As the months went by some aspects of “normal life” returned, and we were eventually able to return to the dojo. Working with a real blade again I gradually noticed changes in my mind and body over a period of many months. Today I have much greater sensitivity to the flow of energy within my lower legs and spine. Adding the Yofuku Enman (腰腹円満) — the advanced tanren practice — to my training over the last year has helped me explore the movement of power from my lower body into the sword through coiling spirals in my limbs. Thirty months into my journey with the tanren, I can viscerally experience what Hida Harumichi described as “the correct center” — a body that expresses kyo and jitsu in proper balance.

Compare these two videos of the deceptively difficult shumpu kata. It’s just a few steps, a draw, and a single cut, but this utter simplicity leaves nowhere to hide and plainly shows the connection (or lack thereof) between sword and swordsman. These examples were recorded almost a year apart. The later recording demonstrates much stronger integration of the whole body with the sword, or ki ken tai ichi (気剣体一).

When my training with Evans sensei began I experienced each part of the tanren in isolation, but now they are all connected by a common framework, one that I feel in my legs and koshi, from the squats of the shōken to the narrow horse stance of the kikō; and from the omoni kokkyu of the daiken to the formation of the hara ball in the peacock and eventual release of accumulated power in the Yofuku Enman. The shodan level of Kurikara Ryu requires mastery of a kata called Jishin (地震), which means earthquake. During Jishin, basic aspects of the tanren come to full fruition with sword in hand. The body and kiai must demonstrate both rooted firmness and explosive power from the lower body without interference or manipulation from the intellect.

I initially sought out the tanren because of what I could sense was missing in my swordsmanship, which I now understand was shinshin renma (心身錬磨). “Renma” means training, but it refers to something deeper, too — a sustained cultivation and tempering over time. “Shinshin renma” then speaks to bringing the mind and body to a state of equanimity, adaptability, and responsiveness. In swordsmanship this manifests in the ability to instantly switch from the everyday mind to combat without sacrificing fluidity or introducing obsessive attachment. This kind of openness is what leads to jiyu jizai in both the dojo and in life.

The restrained rhythms of the tanren have helped my mind and body to slowly open up so that the dynamic extended movements of the sword are accessible without strain. My body is becoming stronger and more fluid and centered, and my mind more responsive and self-aware. The tanren may change how power moves into the sword, but more importantly the practice cultivates sensitivity. After all you cannot do what you cannot perceive.

Although my journey has effectively just begun, my experience with the tanren has strengthened my relationship with the sword and given me deeper appreciation for Battōdō and the potential of our art as a lifelong practice. I am grateful to Evans sensei for opening his dojo to me and I’m privileged to share some of what I am learning with others as we all move forward on the path together.